![]()

Experiencing Anger (Part 1)

Our awareness of anger often does not occur until it is expressed in behavior. The anger when expressed is often brought to our attention by others. The impact of our anger on others may first be realized by the person who is the object of our anger. Have you experienced someone rather suddenly saying to you: “Why are you so angry!” You may be stopped in your tracks by the comment because you may not have been aware of the magnitude of your expression. Often others will see or experience the effect of our anger before we are aware. It is like a reflexive expression which may be instantaneous.

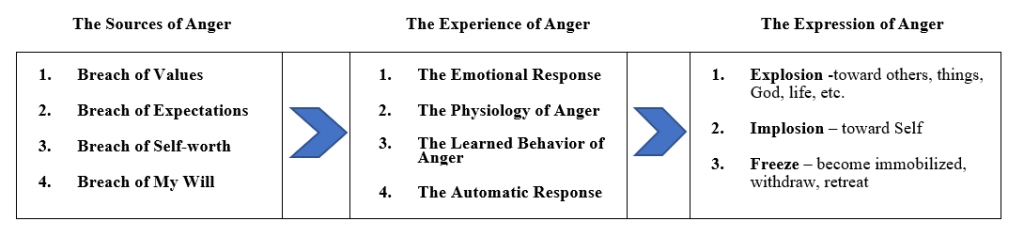

There are mysteries in anger expression. Let’s explore that. It seems to me that the process of anger, or what I would call the “Equation of Anger” has at least three parts. The diagram below will show this analysis. Hang with me and see if this makes sense to you.

The Anger Equation

Glenn C. Taylor

It is “The Expression of Anger” that gets the attention of other people. It may not get our attention immediately if our expression is reactive or the response activated by different kinds of provocation. It is rarely planned or a designed response. We vary greatly in expression. Some of us come to a “boil” slowly, others rather “instantly” hit the high temperature of expression. You probably can see yourself with variable responses which may be dependent on the context.

We also vary as to whether we explode, implode, or freeze. Identifying and acknowledging our typical response in different situations will be important in exploring our anger. To approach the subject with honest means we will have to avoid denial, which is another problem we will discuss later.

To explode is to express ourselves outwardly. To implode is to turn the anger inward toward self. To freeze is to become immobilized which often is expressed as “biting one’s tongue” and often indicates fear of expression. We may assess the situation as too dangerous to express ourselves in the way we would like to. I am sure you have been there! You quickly assess that to express would endanger your interests. Perhaps you will saves it for expression later or to someone who will accept or affirm your anger.

In the next blog, we will look at the “Experience of Anger” to understand the dynamic power which is the heart of the anger equation.

![]()

Experiencing Anger (Part 2)

The previous blog I identified three basic expressions of anger: exploding, imploding, or freezing (withdrawing or becoming unresponsive). We each have our style of dealing with informing others of our anger. Our choice of expression will depend on the degree of safety we feel in the social context. Of course, the depth of our experience of anger will influence the expression. To understand our anger, it is necessary to have the courage to clearly identify how we express ourselves in response to provocation.

Another important contributor to our expression is the pattern of expression learned in our childhood. Family members may typically express anger in the same way. However, personality and the learning of childhood is a big factor. Parents frequently have a great deal of influence. They will vary in how much anger they permit children to express and the manner of expression.

If a parent sends the child to their room if the child becomes angry or frustrated, that provides a strong message. The child, depending of the personality of the child, may come to practice withdrawal or isolating oneself if anger arises. Or the child may learn that the feelings of anger are not to be expressed publicly. If anger leads to shaming or the negating of anger, the child’s understanding of themselves will likely be impacted.

Of course, if the child is ignored in their expression of anger and permitted to continue the expression without attention, they may come to understand that their feelings are ignored and of little or no value to others. One can readily see that childhood is the context in which we learn much about the expression of anger. It becomes very clear that anger expression is something very personal to every one of us.

The context in which we express anger is also very important. You will determine your expression significantly by the context in which you experience it. Certain friends of family members may be willing to interpret your expression as “just blowing off” and as being appropriate. Obviously, their understanding of anger, their degree of agreement with your anger, whether it is directed toward them, or someone they deem worthy of your anger, and the means of expression will all be important to consider.

The creation of electronic communication has great influence on our expression. In the absence of face-to-face contact, facilitated by electronic communication, people express anger, often more effusively, in a more exaggerated form, or with a different tonal expression than if one is face to face. Direct, face to face communication, is usually more controlled and more sensitive to the recipient of the message. One should monitor oneself to understand the degree of difference in our expression of anger face to face or through the screening that occurs through electronic means. How we impact others in our expression is worthy of our intense study. Being open to explore our expression may provide opportunity for us to learn new ways, and more effective ways to express anger. To seek to deny one’s anger is not an option. We were created to experience and to express anger. The question is whether we wish to be more effective.

![]()

The Sources of Anger (Part 4)

Understanding the sources of anger is essential to understanding and controlling the experience and the expression of anger. Without understanding the source, we will be frustrated in managing our anger. All anger is not assumed to be wrong from a Biblical perspective. Paul urges: “In your anger (wrath) do not sin: do not let the sun go down while you are still angry (provoked)…get rid of all bitterness, rage, and anger (wrath).” (Eph. 4:26, 31) Provocation is irritation and is different than rage or wrath. Irritation if dwelt on may lead to harsh forms of anger and requires monitoring. The vocabulary of the Bible is expansive in differentiating the levels of anger.

It is helpful to look at sources of anger. There are at least four sources. A breach of values is frequently a primary source. When your values are breached anger is provoked. Understanding if this is a source will greatly influence your experience and expression. In the Scripture we readily see that when God’s values as revealed, for instance, in the ten commandments is breached, he experiences anger. Think of his response to the overwhelming presence of wickedness when he decided to wipe our humanity with the Flood in Noah’s time. It is important to notice that, first, that ”The Lord was grieved… and his heart was filled with pain.” (Genesis 6:5-8) However, the breach of his values leads to the destruction of mankind. We, too, respond to the breach of our values with anger. Recognizing this to be the case, we choose our response accordingly. We do well to assess our values in determining our response.

Secondly, when we experience a breach of our expectations, we respond with anger. If this is the case, we may wish to examine our expectations to determine if they are appropriate. We might wish to determine if the person breaching our expectations shared ours, or whether they were cognizant of our expectations. Sometimes breaches are in ignorance. Some years ago, two grandchildren (preschool) were visiting our home. My wife informed them that they were not to go near the pond without an adult. A few minutes later, they were at the pond, and scolded for being there. The elder of the two came to me (I was not part of the previous communication.) with a question: “Grampa, can I ask you a question?” I replied, “Yes.” His question was, “What is an adult?” He knew what “big person” meant, but not what “adult” meant. The expectation was unclear, and, therefore, the breach was innocent.

Thirdly, when our sense of worth is breached, we become angry, usually quickly. We may feel unjustly criticized, evaluated, put down, or depreciated in some way. If this is the source of our anger, we may need to do some self-evaluation as to our sensitivity, or to further understand the other’s intention. God’s sense of worth or dignity was challenged by the assumption of Israel that a golden calf was an appropriate representation of the God who brought them out of the slavery of Egypt. God said, “Leave me alone so that my anger may burn against them and that I may destroy them.” (Exodus 32:7-10) Moses intervened. We all experience anger when our person is attacked or devalued. This is a powerful source of anger.

The fourth source of anger I would suggest is when a goal we have is blocked. The frustration of such an experience may blossom into anger. Acknowledging the source of our anger gives us the opportunity to evaluate and determine what the most appropriate response to anger may be. This evaluation will normally lead to a much more appropriate response. Anger experienced and expressed as a kneejerk response is seldom appropriate and may lead to great misunderstanding and deeper hurt. Understanding the source will permit evaluation and may lead to interaction that results in insight that will enable us to respond with more wisdom that reactivity.

In summary, understanding the “Anger Equation” may enable us to become more sensitive to our emotions, aware of our physiological responses, and our learned behavior. Exploring the sources of our anger may lead to much clarification, and the opportunity to determine more accurate ways to cope with our anger. Understanding is much better than reactivity.

![]()

Experiencing Anger (Part 3)

Anger is not only a learned behavior, as we indicated in an earlier blog. It also involves physiological dimensions. The emotions associated have physiological components. There is much literature that elaborates this. Although focusing on the effect of trauma related to mind, brain and body, Bessel van der Klok provides a very helpful book assist in understanding how emotion is expressed physiologically in the body. (Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, Penguin, 2014). It is essentially a “whole body” experience.

The chemical and neurological aspects of anger prepare the body for action. Adrenaline plays a big role along with other chemicals that impact the brain, elevate heart rate, impact breathing, dilates the pupils, and energizes for action. These actions of the autonomic nervous system cause the bodily sensations we experience when we become angry. This prepares us for action, to protect, to run, or to respond with aggression. There are several options for response.

A study of the several words for anger in the Old Testament Scripture are expressive of these bodily responses: to snort or blow through the nostrils (as a charging bull might), a burning sensation in the gut (a precursor to stomach discomfort). Other words identify with wrath, sadness, or annoyance. New Testament words similarly focus on inner turbulence, the flaring of a match, exasperation, a settled inner attitude seeking revenge, or sense of bitterness. Scripture clearly identifies the physiology of anger.

The emotions of anger may lead to aggressive physical or verbal responses that can be very easily overextended into violence. Physical reactions are significantly exaggerated in terms of their destructive potential. Often abusers of other person will inflict great harm in expressing anger. They will frequently say, “I never intended to hurt, maim or injure!” Actions taken in anger are invariably more physically harmful then intended.

The expression of anger manifests out of the emotion, the learned behavior of anger expression, and the physiology of anger. One can readily see the relationship between experiencing anger and its expression as I indicated in the “Anger Equation.” But that does not adequately explain anger. We must look to the sources of anger. The sources are just as individual to each of us as is the experience and the expression. This will be the focus of our next blog.

![]()

The Art of Answering

There probably isn’t a day that goes by when a Pastor is not asked a question that requires answering. Often, such requests are demanding, unsettling, or, perhaps embarrassing.

I want to suggest that there is an art to answering! In fact, often answering is not a good response! That’s right. There are better ways to respond. Unless it is a matter of life or death, or the request for a simple, straightforward answer like, “What is the sum of 2+2?” Most pastors are good with facts, or Bible knowledge. But, even there, there may be a better response.

Consider that many questions have questionable motives. Perhaps the questioner is just trying to avoid responsibility, passing the buck, or wanting a shortcut to thinking through the issue themselves, or being too lazy to do the research. The motives for questions are worth pursuing.

Yes, we like to give answers, we have the knowledge, the authority, the role. Or maybe we just want to display our knowledge, acumen, educational advantage, or the power that comes with our position. Now, that may be uncomfortable to look at our need to give answers, but it may be worth a look.

On the one hand, we can respond by probing, evaluating, judging, or condemning any poor reasons the questioner may have for the question. On the other hand, we would be more effective to seek understanding of the background to the question – it source, urgency, what prompted the query, is it personal or does it involves others, has it been a concern for some time or of immediate concern. There are many possibilities. The result of seeking understanding the question may lead to a very different and more useful answer.

Seeking clarification of the question or exploring its meaning to the person could be of great importance to providing an answer that leads to growth for the person, or a more pertinent answer. For example: “Help me understand the question. Can you help me see what you mean?”

“That is a good question. What does it mean to you.”

“Maybe we should set aside some time to discuss that question in depth. It is important.”

“Let me see if I really understand what you are asking.”

The art of answering may be not to answer but rather to explore in a manner that determines what lies behind the question. Maybe the question is only a place to start and a simple answer may lead to the wrong path forward. Asking and seeking further information may communicate more compassion and open doors that lead to many important outcomes.

Sometimes an answer will lead to the loss of a great opportunity.

![]()

The Wisdom in Answering

The art of answering must come with the wisdom in answering. Peter urges, “Always be prepared to give an answer.” (1 Peter 3:15) The preparation for ministry prepares pastors to answer. But how? The purpose in answering and the how of answering must be with wisdom. People want answers, like those Levites who pestered John the Baptist. “Give us an answer.” (John 1:21)

Much wisdom is provided in Proverbs 15 and 16. Consider the wisdom of Proverbs. It speaks of a gentle answer that commends knowledge spoken by a tongue that brings healing while spreading knowledge. (Proverbs 15:1,2,4,7) The writer speaks of the answer as counsel which gives joy to the speaker and is timely for the recipient. (vs. 24) The answer is to come from a heart of righteousness that carefully weighs the answer. (vs.28)

Wisdom comes from the fear of the Lord and the humility of the answerer. (v.32) The answer of the tongue finds its source in the Lord and will accomplish its goal through love and faithfulness that has been atoned for through the fear of the Lord. (16:1,6) The lips will be honest, and wisdom will appease because it is given in with a lowly spirit and will pleasantly provide the answer being guided by a heart of wisdom. (16:13,14,19,21) The purpose will be instruction given with words that are as sweet as a honeycomb and will being healing. (16:23,24)

The answer must address the issues of the heart and the soul while at the same time addressing the mind with wisdom from the Lord. The responder to the question must come with purity of heart and the wisdom of God. Gentleness precludes argument, challenge, judgment. Our motives must be beyond self-promotion, or the exhibition of superior knowledge. Humility is not easily achieved by those who have had the opportunity of education in the competitive silo of academia.

The pursuit of understanding before answering is explorative, tentative, gentle, and compassionate. Only when the questioner sees our understanding as adequate will our answer by received with reception and understanding. The door to another’s heart is closed by harsh probing, legalistic judging, crush of condemnation. The Jews were “astonished by his answers” (Luke 20:26). If we speak out of love, with the wisdom of God our answers will affect the healing God desires in the seeking soul. And we will know the joy of watching God’s healing in the lives of others. What a joy that is!

![]()

Pastors: Brotherly Support

It has been a privilege to be involved in the lives of thousands of missionaries and pastors over five decades of ministry. My training in both theology and counselling has been helpful in many situations encountered. This has been specifically true for those preparing for ministry.

However, my observation is that in the majority of situations pastoral needs can be met in the ministry of pastors to each other. Pastors need pastoral care that can very often best be provided by pastors. The requirement is a listening, sensitive ear that provides more presence and compassion than answers. This needs to be understood. Pastors are inclined to give answers. Pastors need the presence of another, compassionate listening, and comforting assurance.

Consider the need of Paul, the Apostle. (2 Cor. 7:6f) He was depressed, tired, harassed at every turn, conflict from outside, and fears within. This is not an unusual state for pastors. The literature of research re pastors moving out of ministry bears witness to the reality of this experience for pastors today. Let’s face the fact that seminary training equips us well for everything except what Paul, and pastors experience.

That’s not devaluing seminary training. It is facing the reality that occurs in a pastor’s life after a few years in ministry. It is the “God, who comforts the downcast” that used Titus to comfort Paul. Also, the Corinthian church participated in that comfort. Notice it was the “presence” and the “comfort” that Titus brought. The word “presence” contains the idea of advent (the coming) and the idea of possession. Titus not only came to Paul at his initiative, but in coming he became Paul’s possession, fully owned by Paul in his attention and support. Presence is powerful when it includes these elements. That’s what pastors need. Not advice, not comparison, not competition, not glib generalities but genuine presence, like that of the Holy Spirit about whom the same word is used.

In addition, Paul needed to hear of the “deep sorrow” the believers of the church at Corinth experienced for him. This is a strong word. It describes the agony of Ramah in “great mourning for her children that were no more. (Mt. 2:18) The compassion of churches caring for pastors (yes, pastors of other churches) is a powerful expression of care. This will likely be motivated by pastors who care for pastors. We need to create a constellation of care for pastors if they are to fulfill God’s calling. Pastors who share the need of other pastors must be very sensitive in sharing with their churches.

Pastors caring for pastors is of great importance in the fulfillment of God’s calling to ministry. The sensitivity of a pastor will open the heart of other pastors to be recipients of the ministry that will sustain them in the same way Paul was sustained by Titus. In this process Paul says, “My joy was greater than ever.” Pastors bring joy to other pastors is a worth and necessary ministry for pastors

![]()

Constellation of Companions

Pastors struggle with loneliness. Leadership is a function in loneliness for many. There are a multitude of reasons for this. Most are not good reasons. There is an alternative! The greatest alternative is provided by the practice of the Apostle Paul.

A cursory reading of his epistles clear indicate that Paul was not a loner. In fact, like most pastors, when he was alone, he did not function well. Remember in Macedonia (2 Cor. 7:2ff) he broke down. “This body of ours had no rest, but we were harassed at every turn – conflict on the outside, fears within.” Sounds like the experience of many pastors! Paul knew tensions, the weakness of the flesh, anxiety for those he wished to care for, and apposition from others.

How was he sustained? He was not a loner! He created a constellation of companions. There were at least nine others who stood close to Paul in support. You know their names: Ananias, Barnabus, Luke, Timothy, Titus, Silas, Archipas, Stephanus, and Pheobe. Beyond that group was another circle of support consisting of Apollos, Priscillia and Aquilla, Euodia and Syntyche, Lydia, Mark, and I could and many more to the list. Paul did not stand alone!

He created a constellation of companions. Some were intimate partners in ministry, men and women. Other, seemed to be occasional supporters, perhaps what we would call consultants, or occasional supporters. They were essential to Paul’s endurance and sustaining partners in ministry. This could not have been an easy task as he was frequently mobile in ministry. Some he took with him in presence. Others he communicated with by mail. Others, he simply carried in his heart, knowing their support and prayer for him.

Pastors need to design a constellation of companions with whom they can share, who will affirm, comfort (as Titus did), pray, communicate, and those who visited him, even in prison, to provide the underpinning, assurance of care that he need to survive the rigors of the ministry he was called to endure for the Lord.

Pastor: Can you identify a constellation of companions whom you can count on? Let me challenge you to create a list, as Paul did. If you cannot readily create a list, you are or will be in trouble. No one can effectively sustain themselves by lifting themselves with their own bootstraps. The strong “stand alone warrior” does not engage the enemy alone successfully for long. God never intend we should.

Moses needed Aaron. Yes, it was true when Paul was in difficult experiences the Lord stood with him. Remember in when he was in custody of the Roman garrison and the Jews where plotting to kill him. (Ac.23:11) “The following night the Lord stood near Paul.” And in the dangerous voyage to Rome (Ac. 27:23), “Last night and angel of the God whose I am and whom I serve stood beside me,” declared Paul. He references the first experience again for Timothy, (2 Ti. 4:17) “But the Lord stood at my side and gave me strength.”

God is with us! But that does not preclude setting, as Paul did, a constellation of companions whom we can count on for prayer, affirmation, comfort, support, and to be partners in ministry. God does not intend us to stand alone. Consider creating your constellation of companion for care, and you will celebrate ministry to the completion of the race.

![]()

Faith Confronts Stress

The seeds of stress grow into plants the roots of which are nourished in the soil of our lives. The nutrients that feed stress are many. They include health, relational experiences, behavioral issues, attitudes, emotions, and especially spiritual factors.

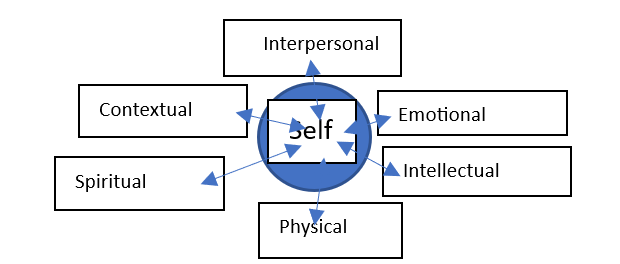

Stress is pervasive. It impacts our entire being. Remember when Pigpen was asked whether his problem was heredity or environment: “It must be environment because it is all over me!” Stress permeates our entire being. We are most preoccupied with the fruit of stress evident in our lives. The symptoms are numerous and painful. However, stress is nurtured by issues that arise in our life experiences. Each person is impacted in several ways.

The Stress Medication Market has grown greatly in recent years. Medications for anxiety states and depressive symptoms have increased by hundreds of thousands of dollars in recent years. We are all affected regardless of race, color, or creed. Check any medicine cabinet. We would be surprised if we tallied our expenditures in one year.

The Apostle Paul got it right when he described his stress: “This body of ours had no rest, but we were harassed at every turn – conflicts on the outside, fears within.” (2 Corinthians 7:5). This is an accurate description. Stress comes from within and from without and its fruit is evident within our bodies and in our relationships. It is pervasive and has many sources or avenues by which it enters our lives.

The Roots of Stress

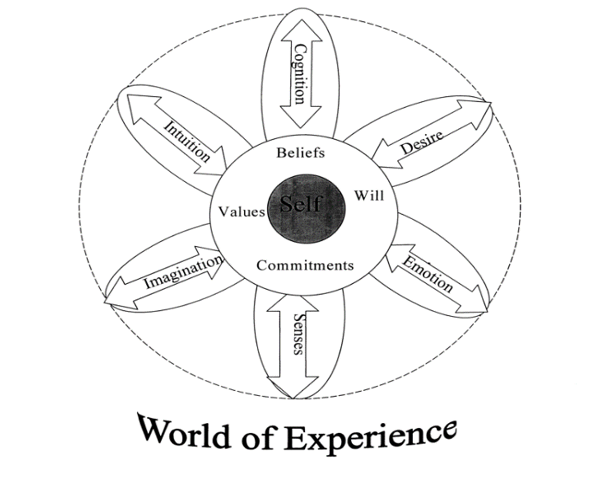

Our world of experience offers several avenues to impact our lives. We live with the pleasure or pain that comes. The input comes from our senses, imagination, intuitions, cognitions, desires, and emotions. Our experience is assessed by what we value, will, belief, or our commitments. The roots of stress are nourished by all of these. These enable us to interpret our experience and thus determine the meaning of the experience. For example, the pain a mother experiences in birthing a child will have a different meaning than pain from a foolish endeavor gone wrong. The cause and the outcome change the meaning of the pain.

The Fruit of Stress

The fruit of stress is evident in our relationships, emotions, minds, and bodies. Space does not permit us to look at these in detail. Let’s look at what the Scripture says about some of these. The tensions that we experience in our relationships are very stressful. James, in his epistle (chapter 4) asks the question: “What causes fights and quarrels among you?” His answer is extensive. First, they come from “desires that battle within you.” He goes on to elaborate. They may be instigated by coveting, wrong motives, friendship with the world, or pride. The answer James indicates is found in our failure to submit to God by drawing near to him and resisting Satan. We must purify our hearts, avoid double-mindedness, and humbling ourselves.

Health issues that arise from stress often require medical intervention, which should be sought early if they are severe. Internal issues may require professional counselling, as will relational issues in many cases. However, much can be accomplished by personally doing an inventory by tracing the fruit back to the sources of stress found in the seeds or the root issues. Focusing only on the pain from the fruit is not a full solution. Addressing symptoms (i.e., fruit) is usually only a temporary solution.

Faith Confronts Stress

James also addresses the issue of how we communicate with one another. The way we speak to one another is crucial. Avoiding slander and judging others is important. Additionally, centering our lives on God’s will and accepting his sovereignty over our lives is foundational. Patience, avoidance of grumbling, seeing the compassion and mercy of God, and seeking him in prayer are all important. Prayer involves confessing sin and seeking healing. Healing issues within our hearts is equally important to seeking healing in relationships.

Another emphasis of Scripture is found in our relationship with others in the community of faith. Everyone needs supportive friends. God did not intend us to stand alone. When Paul was depressed, it was the coming of his friend Titus that brought relief. (2 Corinthians 7) All through the New Testament there is great emphasis on our opportunity, responsibility, and obligation to strengthen, comfort, encourage, and to bear one another’s burdens. (Galatians 6:2) In the same passage, we are urged to “restore” each other gently when another is being tempted. The fruit of the Spirit: “love, joy peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” when pursuit for ourselves and expressed toward others will reduce our experience of stress. It will also nurture the soul in profound ways.

Through the ministry of the Spirit of God in our lives, Jesus will bear our burdens as he invites us to “Come unto me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest.” (Matthew 11:28). We find the comfort we need in our relationship with God whom Paul describes as “the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our troubles.” (2 Corinthians 1:3-7) In this passage, it urges us to extend comfort to each other.

Whether our major stress is from without due to circumstances or from within due to personal issues of attitude, emotions, or worry, the answer to stress is found in our relationship with the God of Comfort and our relationships in a community of faith designed to fulfill the injunctions of Scripture. We may need to address stress at its seeds, roots, or at its fruit. In either case faith confronts stress and invites the resources of God and the community of faith to stand with us in addressing this challenge.

![]()